(Or why I turned Google down)

Seven years ago this month, I started working at TransPerfect. Andy, with whom I had co-owned a small startup a few years before, recruited me for a small technology team here.

When I first joined, I considered TransPerfect to be a temporary gig. I saw it as a way station before I would go on to found my own company. As I started, I learned how the company’s core technologies came together and how the company produced work. I sat with the production and sales groups for a week, working with them, analyzing. I created a list of 11 suggestions consisting of small web apps and information passed via connectors to existing APIs. Together, they would help bridge some of the gaps that I could see causing frustration and pain. My suggestions weren’t taken seriously. As a result, I didn’t feel empowered to effect positive change – and that frustrated me. Moving on to another company seemed to make more and more sense. In early 2012, my boss quit and I started looking for options.

Changing course

Three events in rapid sequence changed the course of my career in early 2012:

1) I met with a senior manager who explained to me that they didn’t value technology. We didn’t add to the bottom line because we didn’t produce revenue. “All tech people were lazy,” they said. “Except you I guess.” (Probably because my jaw had dropped.) I didn’t see that as a ringing endorsement, and I began to look for a new job in earnest. If that’s what one of the most senior folks at the company thought…how could my team succeed? And how could the company succeed given the increasing importance of technology?

2) Because my boss had quit, I began to work with co-CEO Phil Shawe. It was sometimes frustrating. Phil would make a point adamantly. And though he wouldn’t direct me to take a course of action, he’d insist on trying his suggestion. That was fine. What was annoying was that he turned out to be right quite often. I couldn’t understand why – which made me realize that I had a lot to learn from him. The guidance he provided led me to better understand TransPerfect as a whole. I realized that while some senior managers dismissed technology, it obsessed him. He encouraged me to take his feedback, but also to disagree and to try out things on my own. In short, he empowered me to start tackling things I felt were important as well as what he did. I began to knock out my list of 11, rather than waiting on someone else to do it.

3) When I started to put my resume out there, Google started recruiting me. Google is my all-time favorite company. I had introduced my friends to Google in the late 90s after reading a blurb on the small company whose search was “like magic”. I was a Gmail and Chrome beta user. I tried out Google Wave while it crested. I mourned the loss of iGoogle. I have a Google Phone, a Google Home, a Google Chromecast. I tried unsuccessfully to introduce Gmail to TransPerfect. If there was one company, aside from one that I ran myself, that I would jump to, it was them.

The choice

Like LeBron, I had a decision to make. And it wasn’t an easy one.

The encounter with the senior executive lingered. They had made clear to me that I should treat the company as theirs – and that they saw my team’s hard work as waste. But Phil empowered me to treat the company like it was mine. I had a team and the backing of the co-CEO to try to made the company a better place.

So I turned Google down. I had begun to see TransPerfect as the best place to train me to be an entrepreneur.

Over the next year, I rolled out one small tool after another from my list. (I’m using the first person ungenerously. As I’ve written before, I would have achieved nothing without talented partners: Eugene K., Alex P., Chris M., Chris C., Bill B., and more.) Senior developers gave us guidance (thank you, Nils!) but we were mostly on our own.

The first web app we launched was adopted immediately. Within months, two of our tools generated well over half of the company’s quotes. It was clear we had found a need and fulfilled it. The second tool we put out in beta facilitated communication pass-offs between teams. Today, teams use it to exchange over 13 thousand messages a week. As success breeds success, people began to throw more projects at us – and we took on many of these as well.

TransPort

By 2013, my team had completed all but 1 of my 11 initial projects. The remaining one was the most ambitious. To facilitate communication between major apps that were inefficiently integrated.

I wanted to take this project on – but needed a handle to do so. I found it when Phil tasked me with creating a client “WOW” experience in replacing the company’s portal (working with Raja M.)

It was a frustrating ball of competing priorities – and we struggled to get adoption. The road to success began when we brought on the right team. Igor, Leroy, and Iskandar came on to stabilize the development team. And Nathan Gao brought a passion for user experience that transformed the product. (I’m missing so many people who contributed as the team grew – Alric, Victoria, Madhur, Silviya, Lenny, Patti, Anto.)

In the end, we succeeded because the team was passionate, we challenged each other, and cared about the product. From that, came TransPerfect’s 3rd flagship product – TransPort.

Over the past 2 years (as explained at the just-finished GlobalLink NEXT conference), the product grew to over 20,000 enterprise users. Hundreds of companies submitting thousands of projects a week. With just about 100 trainings over all that time. (How’s that for user experience?)

There’s no better graph you want to see as an entrepreneur. It tells you that you’ve identified a need, and that your product fits it. If the graph keeps going on long enough, then it reveals the most important thing: that you have the team that supports the problems of growth.

The TransPerfect model

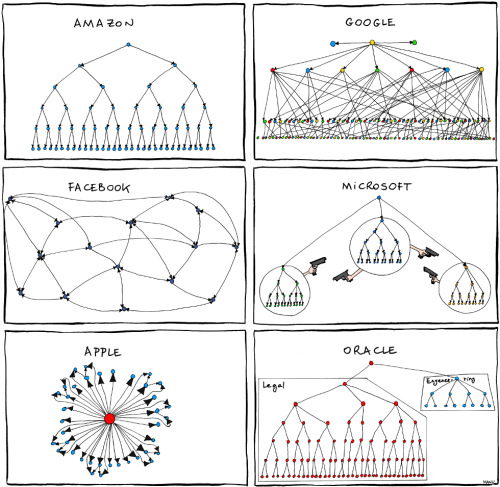

As an aspiring entrepreneur, an “ambitious overachiever”, it makes a lot of sense for me to focus on founding a startup. There are upsides and downsides – but it best fits what I want out of life. That’s true of many people on my team. In fact – when I’m looking to hire someone – that’s one of the things I tell people: We run our team like a startup within a larger company. That is the key to the team’s and product’s success.

Eric Ries writes about this in his forthcoming book, The Startup Way, as a strategy more established companies need to adopt. Reading some of Ries’s interviews, I realized this approach is exactly what made TransPerfect attractive to me – and is what I tried to describe to people I was recruiting for the team.

Phil has managed to apply these principles, hard-won, over his career at TransPerfect – as evidenced by team after team that operates similarly to my own. It’s what has made all the difference over the 20+ year history and is why TransPerfect is now a leader in the field.

At GlobalLink NEXT last week, Phil summarized the core of what has driven the company to succeed:

– Find the best people.

– Align incentives.

– Get out of the way.

That this is what has made the company a success is generally agreed.

I can say that this is what enabled TransPort to succeed, as I applied the same principles to the product. And it is what empowered me to create the team in the first place.

I have always wanted to form my own company. But TransPerfect has offered me the experience of running a startup within a larger company. It remains a great place to exercise an entrepreneurial spirit. And so long as that’s true, I’ll continue to (as we say here of TPT spirit) bleed blue.

* I expect to get some grief for this headline from my colleagues. So be it.