Rory Cowan gave a fascinating presentation at SlatorCon on October 12, 2017 entitled, rather enigmatically, “A Seller’s Journey from a Buyer’s Perspective.”

@Lionbridge‘s Rory Cowan wants to “cure founderitis” in translation industry #slatorcon. Says talk meant for founders in the room. Hmmmm pic.twitter.com/PSslyvIDm3

— Joe Campbell (@j0ecampb3ll) October 12, 2017

He framed his talk as a guide for founders and translation company owner-operators. But in an industry fraught with mergers and acquisitions, it had lessons for everyone.

Cowan’s Tenure in this ‘Curious Industry’

Cowan gave this talk from a position of unique insight. He founded Lionbridge in 1996 and led it as CEO through 20 acquisitions. In 1999, he brought the company public. And then he brought it back private again in a sale to the private equity firm H.I.G. in 2017. (I met Rory when he first arrived at SlatorCon, and with a smirk, he introduced me to a fellow from H.I.G. who happens to also be on the Board of Directors.)

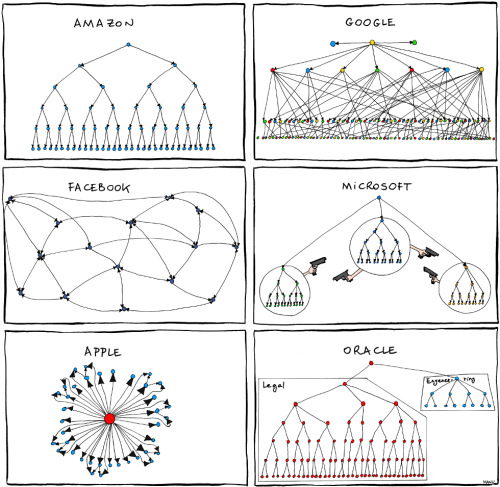

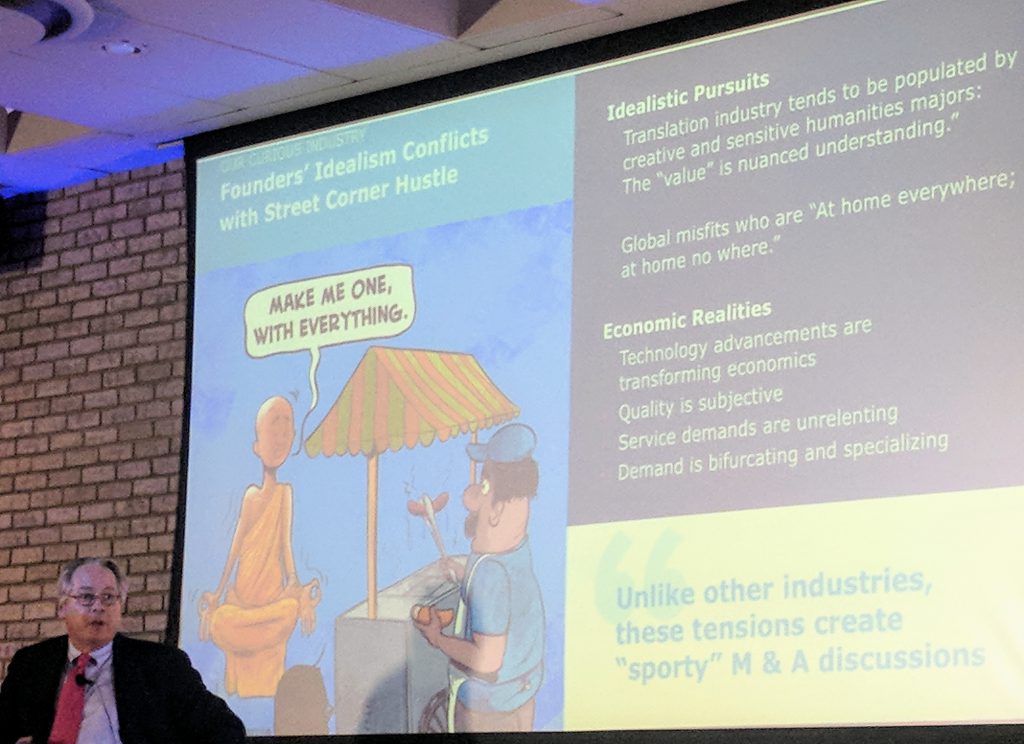

Cowan described the translation industry as unique. He said it in a way that you might talk about a talented but frustrating teammate when you’re trying not to offend anyone. He played up this specialness of the owner-operators in the translation industry, declaring that most founders were “sensitive humanities majors” and “global misfits” who lack “street corner hustle.”

Cowan implied that his success at Lionbridge came because he didn’t have one of those “sensitive majors”, but a Harvard MBA. The path he charted for Lionbridge could serve as a primer for the evolution of the trends du jour in the business world…going public, synergy, outsourcing, crowdsourcing, on demand, the cloud, private equity. In contrast, TransPerfect’s success has often come from New York City hustle: the willingness to work harder, figure out how to do things for the first time, and the willingness to invest in people and long-term projects. I think it’s a stretch to attribute all of this to the comparative merits of an NYU versus Harvard MBA, but there’s a reason that most of Lionbridge’s growth has come from what he called “sporty” M&A deals with owner-operators.

Perhaps the most interesting wrinkle with which to analyze his talk….Much of the team that built up Lionbridge left as the sale approached, feeling frustrated and marginalized – several of them to become my colleagues. But…only a few short months after the sale to H.I.G. closed, Cowan stepped down as CEO after 21 years. I understand that many of his closest allies at the company have been let go by the new owner as well. He remains Chairman of the Board.

Should I Sell?

Cowan said the main question to determine whether you should sell or not was whether you woke up in the morning wanting to go to work. If you don’t, he said, then this was the time to sell – at what he believes is a market peak. He focused on companies that were having trouble scaling – a major problem among the many small to mid-sized companies in the industry. He attributed much of the problem to the founders themselves, as the skill sets that make a small company successful need to evolve in order for the company to keep going. For those struggling, Cowan suggested selling out as a means to cash in and get the help needed to scale.

Cowan emphasized that the process of selling was going to be painful. And it would need to be “endured.” The roller coaster process of Lionbridge’s sale was described in an excellent Slator piece by Florian Faes: as bidder after bidder dropped out, as H.I.G. was accused of “not adequately valuing the company” and “management attention was drained.” The deal did eventually close, but as Florian concluded:

It can be taken as an indication that ownership and top management at leading LSPs consider mega-mergers in the language services industry as difficult to pull off — and post-merger integration, risky.

Cowan gave 3 warnings to any company that might consider being sold. First, be upfront:

Be sure to “Clean up” or proactively disclose all ambiguities before starting process: Buyer WILL find them and they WILL taint value.

Second, there needs to be syzygy, a complementary pairing, between the purchasing company and the purchasee. “Values and culture are paramount,” he stressed.

Third, and the most important thing being purchased, according to Cowan, was “the next tier” of leadership. Buyers need to “risk adjust” the founder’s departure. He explained that this is why it was essential to involve the senior team of the company in the acquisition process. If you don’t, you risk disappointment, he warned.

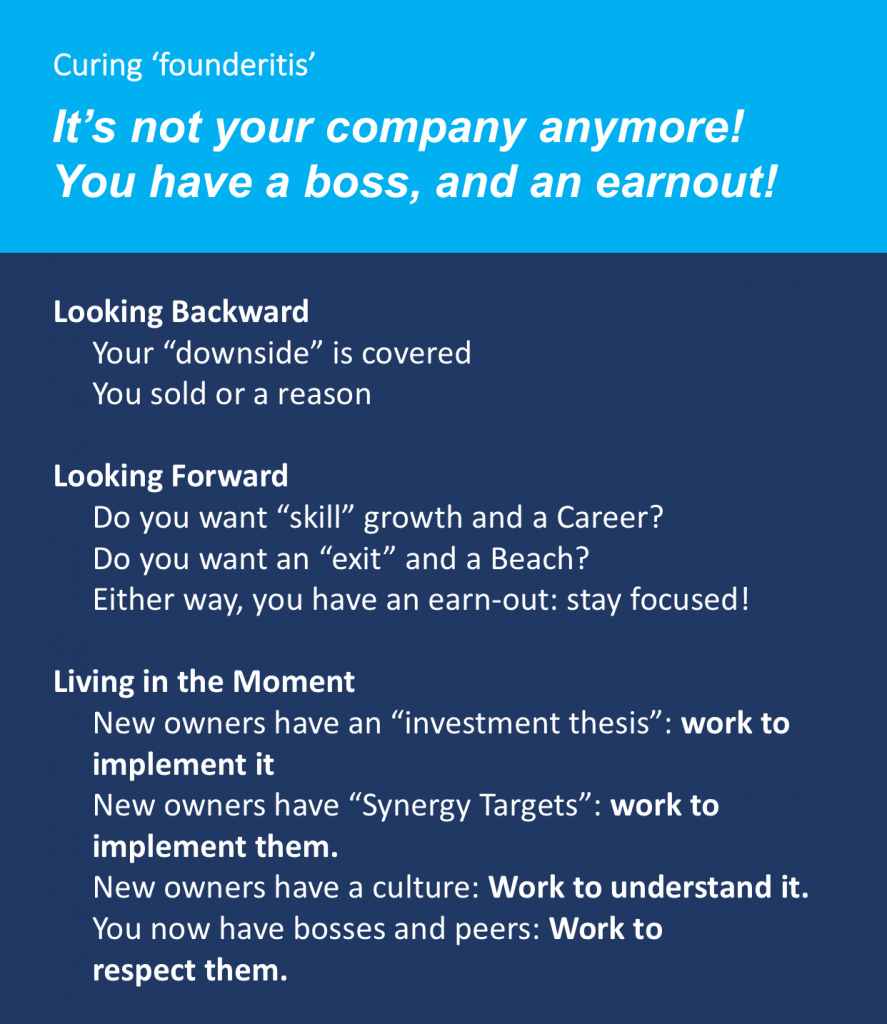

After the Sale: Curing Founderitis

Given that the industry is filled with founders who own-operate their business, and given that Cowan has acquired 20 such business, and that he was recently acquired only to be pushed out himself…he clearly has a lot of opinions on this topic.

He suggested that buyers should do more than simply price in the founders’ departure: it was better them to leave as a way to cure the “founderitis” that he saw afflicting many companies. Only then were companies able to move “from maternal/paternal leadership to business metrics.”

Addressing the 80-odd members of the language industry, Cowan was brutally honest about the costs of selling out though. Here’s my best attempt to recreate his slide:

(Sort of kidding. Cowan didn’t use a meme – though as Renato and I agree, the translation industry needs more memes…)

This for real is my best attempt to recreate Cowan’s slide:

Cowan makes very clear that founders need to get out in an acquisition – or if they stay, that they should become closer to team leads than the founders they used to be. As a founder who was pushed out of his position and much of his handpicked team fired after being sold, I wasn’t sure whether Cowan meant this as a warning or as a positive. Maybe just a description of reality.

He used a rather Harvard MBA term – “Synergy Targets” – as a soft way of saying something. He was more explicit about culture. I thought he even sounded bitter when he described how a sale destroys the culture you have built up.

The ideal seller in Cowan’s world is someone who wants to “exit” and sip Mai Tais on a beach. Because in the end, the point he tried to emphasize to any prospective seller…selling is about losing control.